BC faculty speaks on textbooks

A look into the ways they handle textbooks

Shelfs of books at the BC Bookstore

March 1, 2017

Textbooks have long been a topic of discussion among students in the college system — be it lamentations over their price, their necessity, or their inclusion of materials that would require they be bought new, instead of renting or buying a used book at a lower price.

Those latter materials, be it an included workbook or digital code, are a part of textbooks that many professors enjoy in the courses they teach.

John Gerhold, Performing Arts department chair at Bakersfield College, uses a textbook of his own authorship, “A Plain English Guide to Music Fundamentals: An Outcome Based Approach,” that includes worksheet pages embedded in the book itself.

“Almost every image or graphic that’s in there I made from scratch,” said Gerhold. “This is what is convenient, to have every little bit of written work all in one place at the time you buy the book.”

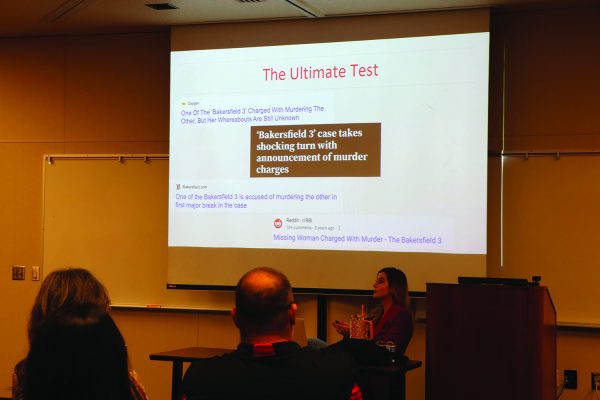

BC Communication professor Andrea Thorson uses two forms of supplemental materials alongside the textbook she co-authored, “Contemporary Public Speaking: How to Craft and Deliver a Powerful Speech,” a workbook and digital code to GoReact, a tool used by students to upload videos of their speeches and give feedback.

“I could videotape you giving your speech, and then we upload it online, and I make it visible to our class and then they get to grade you and say, ‘This is how many times you say ‘um’ or ‘That was a really good thesis statement,’” she said.

GoReact is mandatory for Thorson’s public speaking course, as it is used for grading. If students don’t acquire access with a new copy of the textbook, they must purchase access for $20.

Thorson believes that even though the inclusion of GoReact and the workbook in the textbook package means students are encouraged to buy the $106.99 book new, they’re getting the better deal compared to books used before the one she co-authored.

“Our public speaking books were $180 to $225 and then that doesn’t include the workbook. And if you get the used ones, great, they’re spending $90 to $120. Well, you can get our brand new one with the workbook for about $100. That’s a lot cheaper.”

Thorson also offered the point that the book is resalable to the other “eight to 12” colleges and universities that utilize the textbook, though the GoReact code would assumedly be expired. “They could sell it online easily. There’s no problem with reselling this textbook,” she said.

She also offered the point that many students use Financial Aid to purchase their textbooks.

“Any given semester, between 80 and 85 percent of our students get their books paid for by the government. … They don’t actually pay for their books, taxpayers do.

“If they get it for free, and they want to sell it back for a big profit and they’re mad they don’t get as much of a profit because of the workbook they used in order to get their education … no,” she said.

In this scenario, Thorson questions the student’s intention. “Who’s really being unethical here? The student who didn’t pay for the book but wants to profit from it when the class is done? Does that sound like an ethical thing?”

One source who has been close to the BC textbook process in the past (and wished to stay anonymous) recognizes the benefits of supplemental materials and digital platforms, but believes there is sometimes a better way.

“If the cost is extremely low and the students aren’t going to be impacted in a negative way I would see no problem in a disposable textbook. Now, if the cost is extremely high, I would hope the quality is extremely high, but I would begin to question the disposable nature of the book or the material,” the source said.

When asked what would constitute an “extremely high” price, the source said, “I’m at the point now where anything more than free is too expensive if there’s anything out there that is free and is comparable to what we have.”

Professors across the nation have begun to adopt open-source textbooks (free textbooks found online) in their classes to completely alleviate their students of the financial burden. In 2013, California enacted legislation (Senate Bill 1053), which directed community colleges, CSUs and UCs to form the California Open Education Resource Council, which aimed to build new libraries of free textbooks as well as leverage existing collections like the OER (Open Educational Resources).

“What happened was the state said ‘hey, textbooks are crazy expensive. We need to look into creating an open education resource library.’ And so, this bill went to create an incentive program for colleges to use open source materials, so they created a repository for free materials,” the source said.

According to the source, a lack of pushing has kept open source resources from further proliferation. “A lot of pressure hasn’t been put on colleges to really follow through [to move towards opensource materials],” the source said.

“If it costs money, sometimes you have to sacrifice some of the quality for accessibility,” the source said. “Some instructors who have the academic freedom are not willing to sacrifice that quality. So obviously, they’ll require the book that they believe is of the highest caliber for their students. Which, kudos to them for wanting them to have that type of education experience, right?

“Simultaneously, though, we know that money is one of those indicators which can directly contribute to a student’s success, and success can be defined in all kinds of ways. If you look at the student equity plan, for example, socioeconomic status is one of those indicators of whether a student is going to do well or not,” the source said. “When money is an issue for students, it negatively impacts their progression, their completion, etc.”

The source would “strongly encourage professors, especially knowing the background that many of our students come from, that if there are in fact cheaper or free options to explore that in the summer or between semesters to see if it is something that can be used to help students with the many different things they encounter, one of them being money.”

Ralph Burnette, manager of the BC Bookstore since 2011 and BC student, believes in the importance of rentable materials.

“We’re always pushing instructors to try and make their books rentable because that’s where students are going to save the most,” he said. Burnette gave an example of an expensive textbook in which he was able to negotiate with the department to drop the digital code that wasn’t necessary and make it rentable.

“They just stay in constant circulation. We’ve had them for two years now with about 500 copies, and if you go and compare them to Amazon or anything you’ll find that it’s a pretty good price,” he said. “We’re up to about 67 percent of titles that are rentable.

“And that’s kind of how we roll. We’re always trying to build up rental inventory.” Miguel Garcia, 18, a business major at BC, is currently taking a psychology class in which all of the homework and tests are done through Revel, an online tool made by the corresponding textbook’s publisher Pearson. The service costs $80 for a 12-month subscription, which includes access to the textbook digitally.

Garcia didn’t mind the cost compared to most classes, but recognizes the burden on less advantaged students. “College is expensive, man. You have to buy a lot of textbooks and that’s another $80 on top of it. They have to buy it, and if they can’t then they’re going to have to fail the class.” The current system allows students seeking a lower price on the book through used or rented copies could find it, but ensures the $80 subscription to Revel would still be required. “You can rent [the textbook], but it’s not going to come with the homework because everything is graded and done online. And there’s no way to share the book either,” Garcia said. Garcia has been in classes with a variety of textbook situations. One class offered an open source text completely free, and another required a book he was easily able to secure through the secondhand market. “That’s really helpful, especially in college with all of the stuff you have to pay: gas, car payments, parking passes, everything.”

Another student from the same class, Kathy Lynn Jenkins, 52, went a different route with the textbook purchasing a physical copy due to technological restraints.

“My tablet wouldn’t let me read through the pages, but my phone will. Which is kind of crazy. Some of the stuff in the book, like the graphs and the videos, my phone is too small of a screen for it to display properly,” she said.

Jenkins likes having the hard copy as a backup for the less technology-inclined, but takes issue with the pricing. “I do feel that all the textbooks are insane [in terms of price] if you buy them new.”

Several professors on campus, in pursuit of a better textbook for their students, take matters into their own hands and write custom textbooks.

“The professors here know their students,” said Thorson. What the Communication department found with their old textbooks is that “the Kern High School District doesn’t teach students how to outline. They don’t teach students how to consume a textbook and decide what the important information is and really take good notes that they can do well on a test with. This kind of stuff they’re not taught. But at CSUB we have more students who do that because more of the students were honor students. At CSU Long Beach I didn’t have such a problem with that. If students struggled they got tutors and that was it.” Gerhold holds similar reasons for designing his own book for his music course. “When you use somebody else’s textbook, sometimes you have to un-teach what they were trying to teach.

“I really have a clear idea of what I want the students to know, so putting my own materials together really allowed me to focus in on what I thought was most important for them to know.”

As far as costs for textbooks in the context of the authors, Gerhold said in his case with publisher Kendall Hunt, they are in complete control. “They’re looking to be in the range of whatever else is in the marketplace [for price],” he said.

Gerhold has also felt pressure from Kendall Hunt to be pushing out more editions of his textbook.

In its sixth year on the market, his text is in its third edition.

“The publisher wants me to make new editions more often than I feel is always necessary. The publisher has a vested interested in keeping the book fresh because they make more from it on the primary market (new books). They lose money when it goes to the secondary market — used books and rentals. And so they try to encourage their authors to do more revisions more often.”

Gerhold maintains a policy of releasing new editions only for a good reason. “My attitude is I don’t want to do a revision unless there’s something that either needs to be corrected or added that’s going to make it a better textbook.” He believes the current edition is mostly free of errors.

Textbook authors receive a share of the profits from copies of the book sold. For Gerhold, the money is appreciated, but not why he uses it.

“[The publisher] gets most of it. I negotiated a slightly higher royalty rate of 15 percent. They generally like to offer authors five or 10 percent.”

Thorson also maintains that making money is not the overarching goal of writing textbooks. Thorson and other co-authors in the Communication Department donate part of their royalties to the BC Foundation. Part of the earnings also goes toward a department foundation that gives out textbook scholarships, buys classroom supplies, and pays for professors to attend conferences that present new studies and theories.

“I think we’re doing as good as we can. …We’ve all gone down to as small a portion [of royalties] as possible. …There’s really no way that [the publisher] can sell it for less,” she said.

When asked what her royalty rate is for her textbook before donations, Thorson asserted the question is “wildly inappropriate,” but said typical royalties can be from 6.5 to 11 percent.

“At the end of the day, it’s not free. There are things that have to be paid for,” said Gerhold. “Somebody goes all the way through university to a doctoral degree, they’re probably $250,000 into their education to get to the point that they have sufficient expertise to even consider creating publishable material. That’s an investment in the future of somebody,” he said.

“I think it’s not unreasonable for someone to want to sell some of that expertise. If I could have lived the life I had wanted to and become a recording star, if I made music, I’d want people to buy the music,” he said.

“I respect that students have limited resources. This book is still less than when somebody else was getting the royalty.”

An anonymous source that has been close to the BC textbook process in the past views the selling of self-written textbooks for profit as a conscious decision for the authors.

“I would hope that people are writing to help students better understand and saw that other textbooks in their area didn’t adequately prepare students, and they wrote to clarify those things. Should they be compensated for the work they’ve done? That’s a personal decision. Many people who have contributed to this OER (open education resource), they wrote too, but they thought, ‘You know, I want to give this information away.’”