UCLA professor Eric Avila ends the Hispanic Heritage Month celebrations

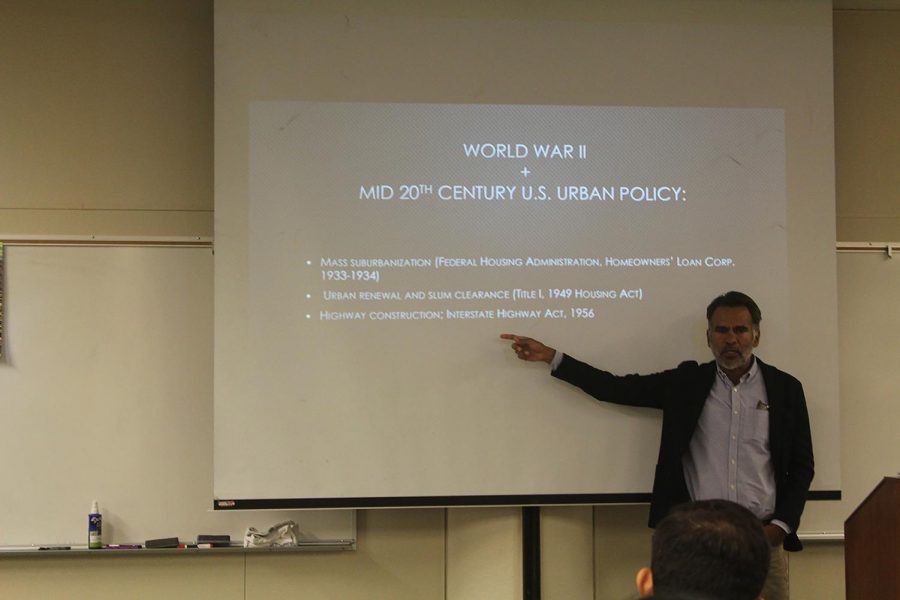

Professor Eric Avila describing government agency associations that formed in the Great Depression era during his speech in the Levan Center on campus Oct. 10.

October 21, 2019

Hispanic Heritage month ends on Oct. 16, which puts an end to the special celebrations held to honor the Hispanic Culture.

Bakersfield College hosted UCLA professor Eric Avila on Oct. 10 in the Levan Center. Avila obtained a doctorate degree in history from University of California Berkeley and is a professor of Chicano studies, history, and urban planning.

While the speech is framed around Avila’s second book “The Folklore of the Freeway,” he took time to explain the aspects he covers as a historian. He classified himself as a Los Angeles historian, this comes from his fascination with cities, and their construction, and the culture of the people that make up those cities.

“LA has always fascinated me, partly because my family history goes back many generations. [They lived] partly in LA, partly in the inland empire,” Avila said.

Avila expanded on the growing population that made LA the nation’s second-largest city. Approximately 200 years ago the population of the city was 3,000 people, now there are over 16 million people that reside in the cities that make up LA, such as Riverside, Long Beach, and those respective areas. His work reflects his study of 20th century structural and cultural events that made LA into the diverse, on-the-go city.

World War II brought many jobs to LA which shifted the city into mass urbanization. Homeowners associations were created, a decade before the war, to promote suburban homeowning.

“World War II was kind of a radical shift for LA. It made LA modern,” Avila said.

Amongst the numerous jobs brought to LA as a result of the war, freeways were also added into the city. The freeway projects began in the 1930s when government agency organizations would go from house to house and take a census of the household. If it was a racially or culturally diverse neighborhood, it was automatically marked as red, meaning that it was unfit for the government to invest in. This deemed the red neighborhoods good for the construction of a freeway.

“If you look at a map of freeways in Los Angeles, you can see that freeways impacted certain neighborhoods in highly destructive ways, particularly urban neighborhoods and particularly minority neighborhoods,” Avila said.

Boil Heights was a very diverse and rich in culture neighborhood that got surrounded by freeways due to it being marked as a red neighborhood. The freeway system gave the government an easy way to rope the minority people into an area of their own.